How To Make A Level

Step 1 - Designer Wishlist

Why does this level need to exist? Every level has a purpose, and it's important to start with the set of requirements that need to be fulfilled for the level to serve its purpose. I like to call this my designer wishlist, like this level is going to be my birthday present and I get to ask for anything I want. I might not get everything I ask for... but if I don't write it down, then there's no chance I'll get it.

I start with things the level needs and cannot exist without. These reasons are usually why you're making a level in the first place. There are many things a level might need, but just to name a few:

- Supporting a specific game type (single player, multiplayer co-op, competitive multiplayer)

- Teaching the player a new mechanic

- Delivering story elements

(If you're having trouble thinking of things the level needs... there's a good chance the level doesn't need to exist!)

As the list goes on, I also write things that the level doesn't need but might be fun and make the level stand out. I might even write things that might be totally unreasonable to ask for. You never know what might become possible as the level develops, and it's important to keep all of those ideas somewhere even if they seem silly at the time.

Step 2 - Molecular Map

Before we even think about what the level space looks like, we need to answer some questions first. What are the major beats of the level? What is the path the player needs to take to get from the start of the level to get to the end of the level? Where does the path branch, and how will it loop back onto the main path? How long should the player spend in each major area of the level?

To answer these questions, we need to think about connectivity and pacing. We're going to do that by drawing a molecular map. If you've ever played Super Mario World (of course you have), think about the overworld map: a network of nodes connected by paths. This is similar to what the molecular map for our level is going to look like. We're going to draw nodes to represent the main areas within the level and we're going to draw paths that connect them. (Using graph theory terminology, we can also refer to nodes and paths on our map as vertices and edges on a graph.)

To answer these questions, we need to think about connectivity and pacing. We're going to do that by drawing a molecular map. If you've ever played Super Mario World (of course you have), think about the overworld map: a network of nodes connected by paths. This is similar to what the molecular map for our level is going to look like. We're going to draw nodes to represent the main areas within the level and we're going to draw paths that connect them. (Using graph theory terminology, we can also refer to nodes and paths on our map as vertices and edges on a graph.)

Nodes, or vertices, represent major beats that the player will encounter as they navigate the level. A node can be a landmark the player will see, a combat encounter, a room with a puzzle, or anything else that makes that part of the level distinct. We can go through our designer wishlist to make sure we get everything the level needs here. It's important to keep everything abstract enough to leave room for designing the space later on, but we can add detail to our nodes by changing the size, color, shape, and more. For example, I like to change the size of the node to describe how significant it is relative to other nodes. We can also use labels and symbols to describe the node in more detail, like putting a star inside a node to describe that there should be a hidden collectible in that area.

Paths, or edges, describe how the nodes connect to each other. By drawing a path between two nodes, we are making a promise that the player will be able to travel directly between these two nodes. Just like with nodes, we can describe more things about the paths connecting our nodes by changing the length, color, thickness, etc. For example, I like to describe the amount of time it takes for a player to travel between two nodes by the length of the path connecting them. Another thing you can do with paths is describe directionality, like whether a player should be able to travel between two nodes from both directions or if the path is only one-way. If your map branches, using a one-way path is a clever way to guide a player back onto the main part of the level.

Remember, do NOT use a molecular map to describe the spatial layout of the map! The purpose of this molecular map is to think about how the level is a network of areas and landmarks that the player will move between. You can also describe in a general sense what the player might expect to find in an area, how long the player should spend travelling between areas, and other abstract metrics. In fact, the more you can go into detail about connectivity, pacing, and flow, the fewer changes you will have to make to your level space later on. But everything should be kept abstract enough that you could potentially design multiple completely different spatial layouts using the same molecular map.

For more info about molecular maps, please check out this rad Gamasutra article. It goes into more detail on designing your molecular maps and it's a very helpful tool!

Step 3 - Spatial Map

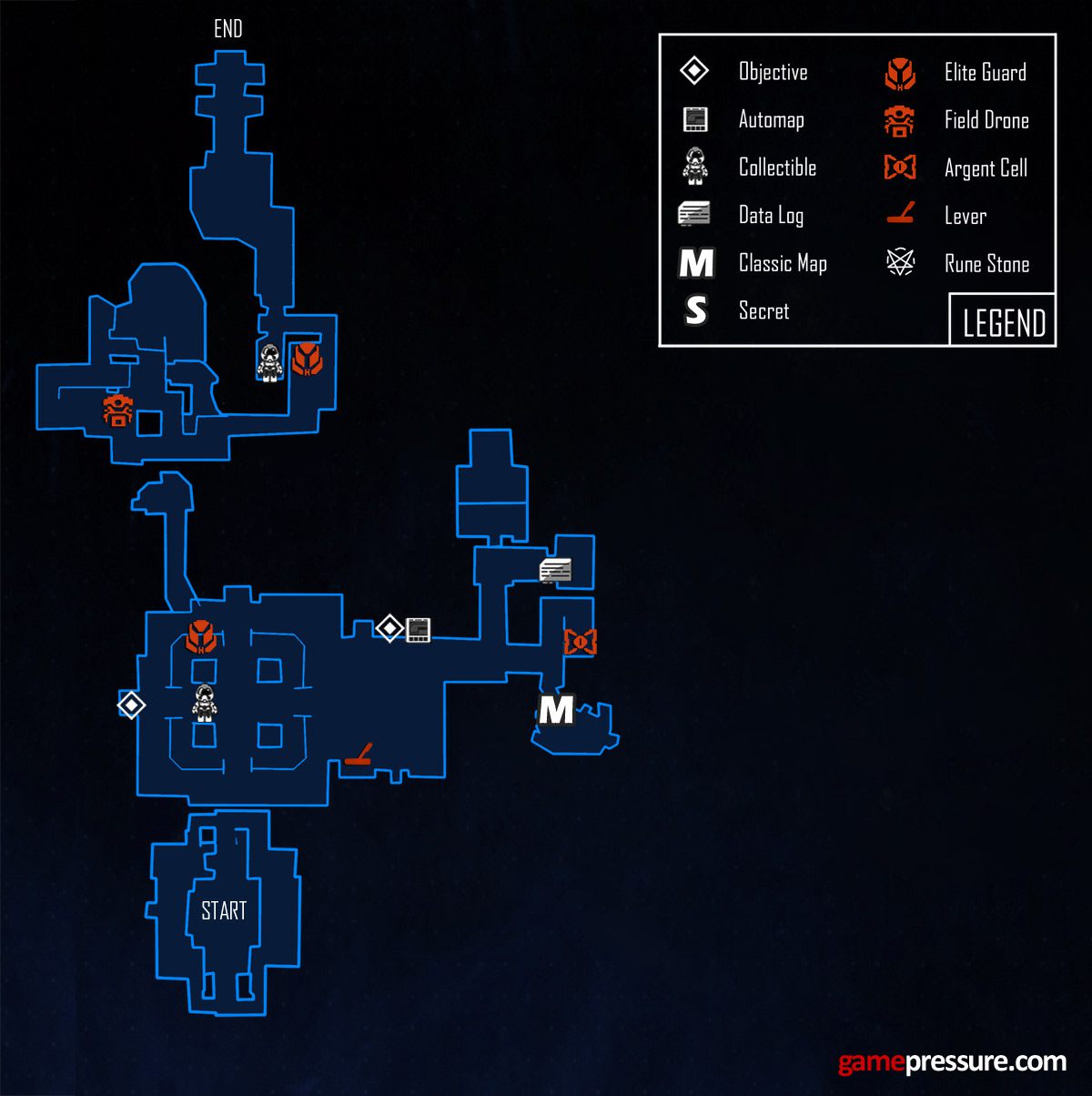

Finally, it's time to draw what our level actually looks like. Using our molecular map, we want to draw a top-down view of the space for our level that abides by all of the guidelines we've established so far. I like to think about the maps I used to see in guidebooks when I was a kid. The top-down maps in DOOM (2016) are a perfect example of what kinds of information should be in your spatial map.

Finally, it's time to draw what our level actually looks like. Using our molecular map, we want to draw a top-down view of the space for our level that abides by all of the guidelines we've established so far. I like to think about the maps I used to see in guidebooks when I was a kid. The top-down maps in DOOM (2016) are a perfect example of what kinds of information should be in your spatial map.

Try to keep a rough sense of scale as you draw your spatial map since we're going to use this exact map as a blueprint when sculpting the landscape for our level. It doesn't need to be 100% exact though. I like to do a rough sketch of my spatial map on paper, then scan my sketch and import it into an art tool like Photoshop or Paint.net and do a finalized digital drawing using my tablet. At the end of this step, you should have a detailed map of your level space that could go in a guide book for your game!

Step 4 - In-Editor Whitebox

Now that we have a spatial map of our level, it's time to start building our level in an editor. It doesn't matter what engine you're using as long as you have tools to edit a level and you can play the level to test it.

To start designing our level in the engine, we're going to place our spatial map in the engine.

At the end of this step, you should have your entire level built in the editor using only simple geometry and textures. The landscape should be rough and unpolished, structures should only exist as untextured (or only using simple color textures) primitive shapes, and scripted events should be functional but simple. The level should be technically playable from start to finish, although a player might get lost or need help to know what to do along the way.

Step 5 - Playtest & Iterate

Hopefully along the way up until this point, you've been showing your level to people and getting their thoughts. Playtesting is always important in the design process since it gets a fresh pair of eyes on your design to point out flaws you might not be able to see. But now, playtesting becomes mandatory. You need to get players sitting down in front of your level and watch them try to navigate it. Don't wait until your level is almost finished to show it to people because then it's too late. The purpose of testing is to find mistakes and make changes.

There's tons of things you might want to change about your level as you playtest and iterate on it. Here are a handful of important things you should be considering with each new iteration of your level:

- Player Goals - At any point in your level, what is the player trying to do? Do they know how to do it? If a player is frustrated, it's likely they don't know where to go or they don't know how to get to where they want to go. Make sure you're giving the player information about how you want them to move through the space.

- Scene Composition - During any particular spot within your level, what can the player see and hear? What do you want the player's attention to be focused on, and how are you drawing their attention to it? What's in the foreground, midground, and background that will influence the player's understanding of the space? This is a great tool for establishing player goals, since you can frame the goal the player should be going for and show them how to get there. If you want to see some insanely clever scene composition examples, look no further than The Witness.

- Area Boundaries and Transitions - What are the identifying characteristics of each area? Can the player identify all of the different areas from your molecular map? Do the paths connecting nodes transition between them smoothly? Additionally, make sure your level is built properly so that the player can travel along all of the paths you specified in your molecular map, and only those. The player shouldn't be able to break boundaries to travel between two nodes that shouldn't be connected or leave the map entirely.

- Engagement - At the end of the day, you're making a game to be enjoyed by the player. So listen to your players. Is the level fun to navigate through? Are the obstacles too easy or too hard to overcome? Is the player exploring the map and finding secrets, or are they sticking to the main path so they can be done with the level faster? If the player isn't having a good time in your level, it might help to ask what they would change about the level if they could. You shouldn't change your level just based on the wishes of one player, nor should you take the player's suggestions at face value. Analyze their feedback and figure out what they're really trying to say, then come up with a solution and implement it.

This step is by far the longest step out of this whole process since you'll be repeating it many times. AAA games go through this process dozens of times to make sure their levels are perfect. It's easy to get discouraged as you iterate; you might feel like your level isn't getting any closer to being finished or players aren't having fun in your level. Just remember that each playtest helps you learn more about your level and each iteration is another opportunity to get closer to where your level wants to be.

At the end of this step, your level should fulfill all of its purposes from your designer wishlist. A player should be able to navigate through the entire level in the way you want them to.

Step 6 - Environment Art & Sound

If you've been following the steps correctly, your level should be fully built and playable to your liking from a gameplay perspective. However, your level probably looks and sounds like garbage. It's time to put away the sculpting tools and get out your paint brush.

This is where you add the little details that make the level feel more alive and immersive. You might do this yourself or you might pass off your level to an environment artist or sound designer. If doing the latter, it's vital you communicate your design intentions to the artist or sound designer. Share your designer wishlist, molecular map, and spatial map with them to make sure they understand how the level is supposed to be laid out. Ideally, the artist or sound designer isn't editing the landscapes or structures in your level at all. After all, you just went through tons of work to make sure everything was perfect. Make sure that their work doesn't jeopardize any of the work you put into your design. (But remember to be nice to your artists and sound designers! They want the level to be just as enjoyable as you do!)

At the end of this step... congratulations! You've finished your level. It's a masterpiece ready to be played and enjoyed by players all over the world. Pat yourself on the back, grab some ice cream with your artist and sound designer to celebrate, and then get to work on the next level!